Childhood Years in a Japanese Prison Camp

Interview with Anne-Ruth Wertheim

by Harry de Ridder 21 augustus 2010

Anne-Ruth Wertheim was born in 1934 in Jakarta in the former Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. How did she perceive her youth?

I lived with my parents, my sister and my little brother in a beautiful home and perceived the world the same way all children do – it just was the way it was. My life was idyllic. We would play outdoors almost all the time, climb trees and play games on the shores of the duck pond in front of our house.

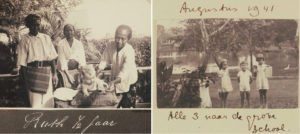

Starting at the age of three, I went to a nursery school and after that I went to primary school. I was barely aware that virtually all the children there were white until I went to the kampong one day for our chauffeur’s wedding. I saw a lot of Indonesian children there, they were running around barefoot, something we were not allowed to do. It did not even enter my mind to wonder whether they had any shoes.

In the vacations we would go to the mountains where it was nice and cool, you even had to sleep under a blanket there. The blanket smelled slightly of camphor, an aroma I still associate with being off from school, the mountain air, and having adventures.

What did Anne-Ruth notice about the class difference between the white Dutch people and the Indonesians and Chinese in Indonesia?

There were always Indonesian servants around who were quick to pick up anything I dropped. They would take my dirty clothes and give them back clean and neatly ironed. At breakfast every morning, my mother would sit at the table and talk to Kokki about what she was going to cook that day, Kokki squatting on the ground next to her as they spoke. And when I was allowed along to go shopping, I would see Chinese proprietors bossing around Indonesians who swept the floors.

My worldview consisted of three layers: on top were we white Dutch people, at the bottom the Indonesians, and in between the Chinese.

Anne-Ruth at six months old and the Indonesian servants (left) and Anne-Ruth and her sister and little brother (right)

Starting at the age of seven, Anne-Ruth spent several years in Japanese prison camps on the island of Java. How did these childhood years in the camp affect her?

From one day to the next, my world was turned upside down when I was seven years old. The Second World War was raging in the Pacific and the Japanese occupied the Dutch East Indies. They set up a cruel regime that was to last for three and a half years. They put us and all the other white people in prison camps. We hardly had anything to eat and not much of anything else either and were kept in line with a show of physical force. Our camp was guarded by Indonesian soldiers who were beaten by the Japanese just like we were, but they had enough to eat.

Now the Japanese were on top, the Indonesians in the middle and we whites all the way at the bottom.

After experiencing myself what hunger, deprivation and racist violence mean, I started wondering. My privileged position as a child of colonial parents was no longer taken for granted. I started to understand how other people had to live, what poverty meant and how you are influenced by images you have in your head about other groups. Did higher and lower groups actually exist, and what good did it really do you?

Since we children lived in among adults day and night, young and old women and mothers, I started to understand the relationships people have with each other. I saw how people could pester each other and take out their frustrations on other people, often their own children. But I also saw how, despite everything, many of the women preserved their dignity, protected their children and defended them like lionesses and helped and supported others.

Among us children, there were also some who did a lot for others. And I saw how much influence gossiping has on how people think and feel about each other. I realized prejudices that circulate about certain groups get stuck in people’s minds and have a destructive effect.

The moment came when I was very angry at all the people outside the camp all over the world who were free and just left us there. I decided that when I was older, I would do my best to put an end to injustice, see to it that not as much emphasis was put on the differences between people, and that they respected each other more. I was going to make sure everyone lived together in peace.

I don’t recall that we children ever talked about this or that I ever spoke to my mother about it. But after the war, when my parents found each other again, it turned out they had both independently arrived at the conviction that the Indonesians had a right to their independence. The Dutch should live and work with them as equals. From then on, that was simply the way we felt in our family, and it led to a lot of aggression from other people. Because most of the Dutch were still thinking like colonials.

What did Anne-Ruth observe about the daily routine in the prison camp?

We were so hungry, it was so awful I still often think about the horrible stomach cramps we would get and how we would think about food all the time, there was no getting around it. If you got sick, there wasn’t any medicine so adults just died and so did children. I was so scared something like that would happen to me or my family or my friends.

There was also the constant violence on the part of the Japanese prison guards. The worst thing of all was that my mother, who was supposed to protect me, was sometimes so visibly afraid herself.

But we children still spent a large part of the day playing, just like before, outside the camp. Groups of us used to scout out other parts of the camp – after all, there were about two thousand people living inside the fence and there were all kinds of things going on. Or we would go have a look at the garbage dump. There was broken glass there and all kinds of other sharp objects. But we children, who had not had shoes for ages, had such hard calluses on the soles of our feet we could just walk right over everything. We found all kinds of things there and if you saw something you wanted, all you had to do was shout chupe and it was yours.

There was a lot of bartering in the prison camp, how did that work?

The camp was guarded by Indonesian soldiers. They would sit in bamboo towers at the corners of the prison camp, their machine guns ready to fire. My mother always said it was not a good idea to look up because if you attracted their attention, it could be dangerous.

Since they were beaten by the Japanese just as often as we were, they sometimes tried to run away to their villages and families. It was not simple though because their heads were shaven and all they had was their khaki clothes so they were easy to spot. A couple of times a day there was a changing of the guard and you would see one Indonesian soldier come down the stairs and another one go up. When they changed places, there was a second when the Japanese couldn’t see them, in between the double fence of mats and barbed wire that kept us in. That was when the bartering went on between the Indonesians and us. They gave us some of their food and we gave them clothes so they could get away. Ladies’ pajama pants with the legs rolled up were still better than their own khaki cloths.

Of course all this bartering was strictly forbidden. The Japanese were enraged when they found out and their punishments were horrible. So most of us didn’t dare even think about it, no matter how hungry we were. But some people went ahead and did it anyway and put the entire camp in danger because the Japanese would often punish the whole camp for what one person did, even if that person was a child!

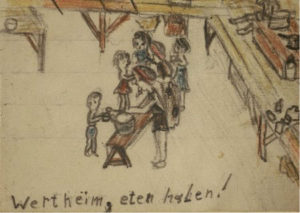

What happened in the camp that made the most impression on Anne-Ruth?

The penalty roll call. They had us all stand in the tropical sun for a whole seven hours without food or water. Some Indonesian guards had escaped and they caught them. A pair of pajama pants was suspended from a pole and they kept shouting Whose are these? Whose are these? They wanted to get the person who had exchanged the pants for food and punish him or her. At first no one said anything. They took the elderly and the sick and made them stand in the sun. Still no one was talking so they started beating the Indonesians who had escaped right in front of us. My mother didn’t want us to see and she pushed me in between the other women so all I could see around me was their legs. But I heard the screams of the Indonesians. In the end, one of them pointed her out. Her name was Non Lies. He said, ‘Kassian, Non Lies,’ which means ‘Poor Miss Lies.’ She was taken away and never came back again.

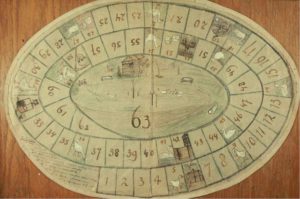

In the camp Anne-Ruth’s mother drew a Goose Board for the children. Anne-Ruth later said the Goose Board was a symbol for everything that happened in the prison camp. Can she explain what she meant by this?

Playing in general and playing with this board game in particular was a way to escape from the misery in the camp. For a little while you were in a kind of make-believe world far away from reality. All the things that happened to you on the board stood for things you experienced in daily life. Your dice could bring you bad luck, like on the days when there wasn’t enough to eat for anyone and you didn’t get anything at all or only a little bit. Or when one of the Japanese thought it was the right moment to start beating someone and you had to stand there and watch. You could also be lucky with the dice, like when your friends were particularly nice to you. Or when you had a chance to read a good book. There hardly were any books, and we used to lend each other everything we had. So sometimes you had to read the same book again and again, but we didn’t mind. After a while we could recite whole passages by heart!

The Goose Board also gave us the illusion that at the end of the game, you would be home again at our house on the duck pond. Instead of what is usually on a Goose Board, my mother drew things we were familiar with at the camp. The watchtowers, the prison itself, the gate, the camp store and the well. And of course Death was on it too, but that is just part of the regular Goose Board.

Anne-Ruth wrote a book about the time she spent at Japanese Prison Camps and called it The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks. Can she explain the title?

The way I interpreted the Goose Board in The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks went further. I associated it with the beautiful picture my mother drew in the middle of the board of the duck pond with our house in the background. She drew from memory when she was in the camp. On the shore of the pond, actually more of a lake, she drew my sister, my little brother and me feeding the ducks. On the drawing you see a big nasty goose trying to snatch the bread away from the ducks and in fact that was what always happened in reality.

The nasty goose is a symbol for the Japanese, the ducks are symbols for theoppressed Dutch and Indonesians

In my story the goose stands for the Japanese oppressors and we Dutch are the ducks, together with the Indonesians, who also suffered a lot under their regime.

In 1944 Anne-Ruth’s mother was confronted with a serious dilemma. Can Anne-Ruth explain the dilemma her mother was faced with and the decision she and the children made?

Half way through the war the Japanese, who were allies of Nazi Germany, started to follow their example and separate Jews from non-Jews. My father, who was in a men’s camp, was Jewish but my mother, who was with my sister, my little brother and me in this women’s camp, wasn’t Jewish. So we children were half-Jewish and the Japanese were threatening to violently separate us from her. To prevent that from happening, my mother decided to register as Jewish herself so we all went to the Jewish camp together.

On 4 September 1944, the camp commander had a special order for us. Everyone who had even one drop of Jewish blood had to register to be sent to a separate camp. My mother was scared out of her wits because we had Jewish blood. Everyone had assumed it would only be the Germans who persecuted the Jews. But the Japanese imitated them.

My mother couldn’t sleep at night. What was she supposed to do? She herself was not Jewish but my father was, so we children were half-Jewish. If she told the truth, there was a chance she would have to stay and we children would have to go to the Jewish camp without her.

After the special order about Jews, my mother spoke to us about what to do. I really enjoyed being treated like an adult like that. It had never been like that before the war. My parents used to have long private talks and we didn’t understand a thing.

Should she keep it a secret that we were half-Jewish? It was a gamble, we didn’t know what would happen. Maybe my father had kept it a secret in his men’s camp. But what if he was registered there as Jewish? Then they would know. Or what if someone betrayed us? Or if they started checking for Jewish names?

In the end my mother decided she would also register as being Jewish herself. So that made us 100% Jewish and she would go with us to the Jewish camp. And that is what happened. We had to report to the gate early one morning and were taken away in a lorry with all the other Jews.

In 1944 Anne-Ruth and her mother, sister and brother were moved from the first camp in Kramat to another camp. What differences were there in how she saw the two camps?

Before the war the Jewish camp in Tangerang had been a juvenile prison and that is what it was again after the war. Two thirds of the camp population was Jewish and one third wasn’t. The groups were housed in separate parts of the camp, but in such a way that there was some contact between them. The prison was made of dull grey concrete and it was grim and glum. We slept in halls with eighty people in bunk beds. The halls had bars on the windows and the doors were locked at night. So you couldn’t go to the toilet at night and constantly heard people going in the buckets on the floor. We got even less to eat than in Kramat, the camp we came from, a fenced in neighborhood in one of the poorer parts of Jakarta. Even though seven of us lived in a tiny room there with three bunk beds, you could walk

around the houses and there was a bit of space outdoors where you could play.

Anne-Ruth referred to the situation in the Japanese prison camp where you were discriminated and at the same time you discriminated against others. Can she explain what she meant by that?

There were Western Jews in Tangerang and also Jews from Iraq, Baghdad Jews. In The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks I called them Eastern Jews. They had initially come to Indonesia as a mercantile minority. When the Japanese invaded Indonesia, they were imprisoned, just like us, and now they were in the separate camp because they were Jewish. They looked like Arabs, spoke English, and lived together in a few of the halls.

We never played with them and used to gossip about their weird customs and how they used to steal, but we never actually checked that. We used to curse at them and they cursed at us. If I am honest, I have to admit we discriminated against them. That is strange, we were discriminated against ourselves and yet we did the same thing to others. Or is that only logical?

Anne Ruth went to Indonesia for the third time in August 2010. This might sound trite, but which nostalgic spots meant the most to her?

This time my husband and I went to Indonesia with my middle daughter Dorothee, her husband Harry and their sons Milan and Ramon. They wanted to see where I was born and where I lived until I was eleven. We started with where the camps had been. Kramat is still there and is now a pleasant district with busy streets lined with little shops and friendly Indonesians who immediately recruit older people who still speak Dutch to converse with us.

In Tangerang, now a large suburb of Jakarta, the prison is still there and is once again being used as a juvenile prison. The prisoners are now very young Indonesian girls who were drug dealers. We talked to them through the bars and felt sorry for them. At the spot where the kitchen used to be and the tiny bit of food that was supposed to keep us alive was dispensed every day, there was now a large reception hall they proudly showed to us.

Of course we also went to our old house on the duck pond. I showed my grandchildren the spot on the shore where we used to play Heaven and Hell, a game we made up ourselves, with the Catholic Chinese children from the neighborhood. That was when we were not in prison yet but most of the Dutch children already were. We still didn’t have any contact with Indonesian children at the time, they lived far away in kampongs on the outskirts of the city. Of course there was no school any more, so we were free to do whatever we wanted all day long.

It wasn’t really a carefree time though because our father was in prison starting the first day of the occupation and we always felt the menacing presence of the Japanese in their military uniforms. We were scared stiff whenever we saw them coming that it was a raid and they were going to send us to a camp.

And one day that is exactly what happened. It was in the early afternoon and all the adults were taking a nap. But we were playing at the duck pond and we watched it happen. The soldiers banged on the shutters of our house with their rifles and my mother appeared at a window, disconcerted. We were given until the next morning to pack our things. Then we were taken to the Kramat camp on a flat cart pulled by a horse. Our Chinese friends waved goodbye to us.

Has Anne-Ruth ever told her story to Indonesians?

It just so happens I was invited to come give a workshop about The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks at the Writers and Readers Festival in Ubud, Bali in October 2010. The international festival in Ubud is held annually. This year the theme is Harmony in Diversity, a theme I really care about!

I did tell my story to Indonesians in the form of the Indonesian translation of the book, and 700 out of 1,000 copies have already been sold!

Box

This interview is based in part on the book De gans eet het brood van de eenden op, mijn kindertijd in een Jappenkamp op Java (The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks, my childhood in a Japanese prison camp on the Island of Java). The book was published in 1994 and can only be purchased at Linnaeus Book Shop in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. An Indonesian translation was made by the well-known Indonesian author Hersri Setiawan in 2008 and published by Galang Press in Yogyakarta.

A Japanese translation is to appear soon on the Internet.

At school

Classroom material under the same name was published by the Centre for World Education in conjunction with Anne-Ruth Wertheim www.cmo.nl/gans . The material consists of two different classroom letters, one for the 10- to-12 age group and one for the 12-to-15 age group. The classroom letters go with a CD that tells the story of The Goose Snatches the Bread from the Ducks, spoken by the author. The classroom letters can be downloaded in a pdf.

The CD can also be heard and seen at the Website, both in Dutch and in English.