When I was in our first Japanese internment camp for about a year, I experienced something that made an immense impression on me. I was nine years old at the time and it has stayed with me all my life. When I was over seventy years old I carved out of stone three sculptures that refer to this event.

The Indonesian who had stolen opium

Anne-Ruth Wertheim

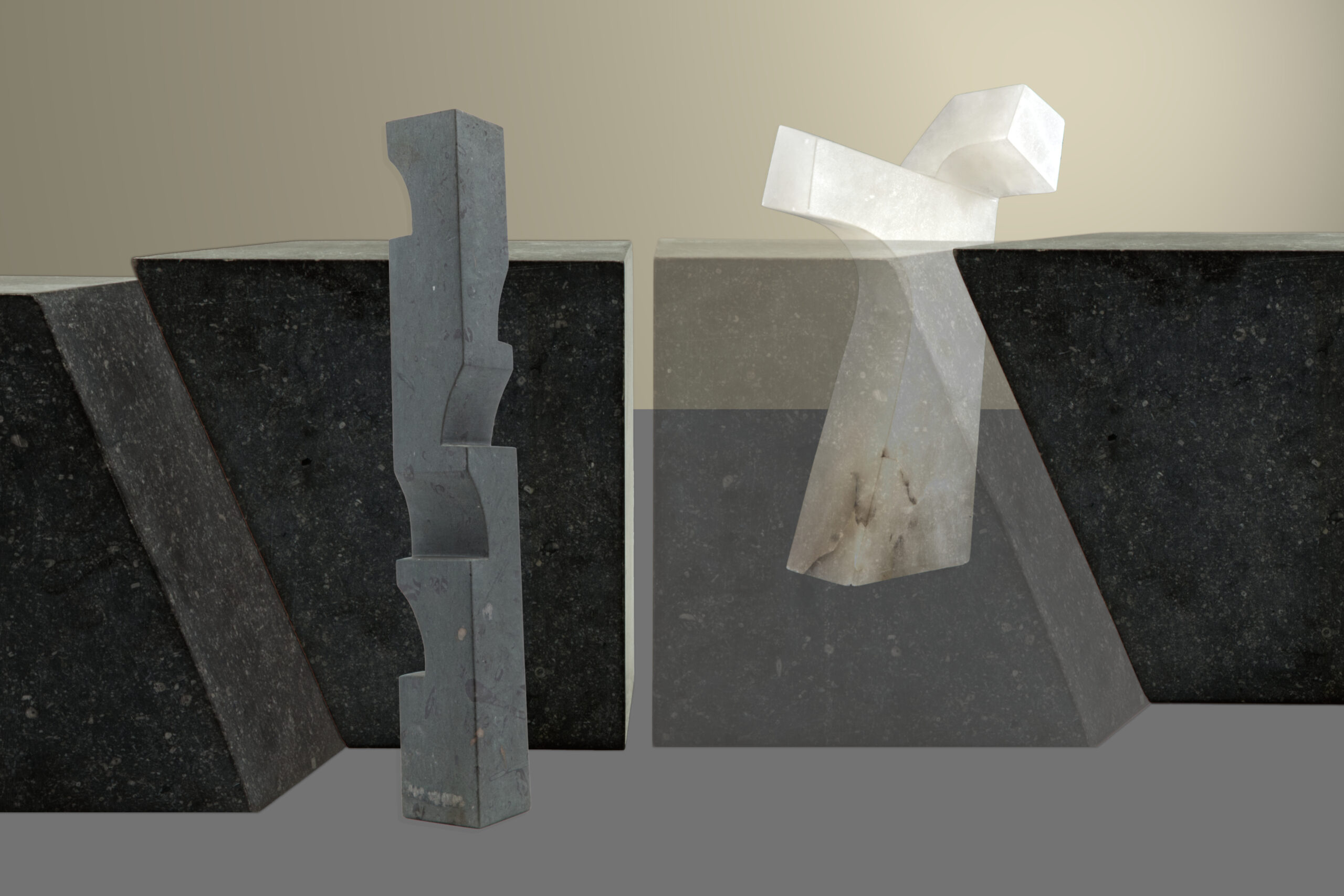

I made this photo collage together with Peter Hessel, designer of my website.

This photomontage shows three sculptures: over the full width a solid wall with diagonal and vertical openings in it; in the foreground a tall, angular spiral staircase with upward curves under each step; and behind the wall a whitish ‘gallows tree’. The three stone sculptures were carved by me: the wall in Belgian bluestone, the staircase in Anröchte limestone, and the gallows tree in alabaster. Together they refer to an event from my childhood that I will describe here.

I was nine years old, and my mother, sister and brother and I were in a Japanese internment camp in the centre of the former Batavia (now Jakarta), the capital of the Indonesian archipelago. When I was a child it was a Dutch colony known as the Dutch East Indies. The reason we were in a camp was that the country had been invaded and occupied by the Japanese some years earlier. They immediately began to detain the previous rulers – us Dutch people – in camps, with the men separated from the women and children.

In the camp: children playing on the street

Our camp, called Kramat-Zuid (‘South Kramat’), consisted of a few streets that were sealed off from the outside world by a fence that was guarded by armed soldiers. So we lived in ordinary houses, but were crowded together with a very large number of people. In our room there were three bunk beds and an ordinary bed, for another woman was also living there with her two children. The occupants of each house had to make do with one toilet and one bathroom. We were given far too little food, and twice a day we had to attend roll-call in a large space in the middle of the camp, where we were counted and had to bow to the Japanese; cruel punishments were meted out whenever any of us did something we shouldn’t, and then we were all made to watch, as a warning.

But, oddly enough, there were also some nice things. The Japanese had closed down the schools, so we had the whole day to ourselves except when we had to do forced labour: sweeping or working in the kitchen garden. It was always hot, so we could play outdoors, in the street and round the house, without having to wear shoes. We hadn’t had shoes for a long time; either we’d grown out of them or they were worn out, and there was nothing to repair them with. We played tag, hide-and-seek or cops-and-robbers, changing the rules as it suited us. There were no toys left either, so we never had to argue about who could play with what; but we did argue about which group you could belong to. We roamed through the camp in groups, if possible to the far end, pretending we were on an expedition or trying to free a prisoner. Sometimes we ran into a Japanese guard, and then we had to jump to attention and make a proper bow.

My mother fell seriously ill several times and was admitted to the camp hospital – a house just like ours with several beds to a room, one doctor and some nurses. There were no medicines, so I really don’t know how people ever got better. Whenever our mother was there we stayed a few houses down the street with a friend of hers, Bep Rietveld, whom we called ‘auntie’. She was an artist, and drew pastel portraits of children in the camp (1, including the three of us. Whenever the boys were moved to a men’s camp at the age of ten – the Japanese then considered they could make women pregnant, and so were adult men – she also drew portraits of them, so their mothers could at least remember what their sons looked like. When her own son was later taken from her, she was distraught; no-one knew which camp the boys had been taken to, and we never heard from them. Fortunately my brother was still under ten.

People gossiped about our aunt, which made my mother very angry. Bep was considered eccentric and was often criticized, especially because she was so untidy. It was true that she couldn’t care less about clearing things away, and you could see that when you stayed with her. But I loved being there. And it was amazing that she could fit the three of us into her single room, as she had three children of her own to look after. Only sleeping was a bit of a squash, as we had to share beds. Every morning she would wake us with a cup of sweetened tea which she handed us in our bunk beds, even if we were in the top bunk.

When roaming through the camp we tried to stay as close to the camp fence as possible, so we had some sense of freedom. The fence consisted of bamboo poles with braided bamboo matting and strands of barbed wire in between. The fencing behind the houses in our street cut the back gardens off from the outside world. To follow it we had to crawl under small fences to get from one garden to the next. Eventually we got so curious that we decided to make a spyhole in the fence behind our own garden. We did it very carefully so that we could close it up again and the grown-ups wouldn’t notice.

bamboo watchtower

What we could see through our hole was a large open stretch of grass with a tall tree in the middle, and a long white building in the far distance. We imagined we could escape if we just made the hole bigger, and immediately began arguing about which of us could go first. But of course escape was not an option. To begin with, there were tall bamboo watchtowers at each corner of the camp, with guards who kept their rifles trained on us day and night. Our mother always warned us not to look up – it was dangerous to attract their attention. And outside the camp we would have stood out with our white skins among the Indonesians, Indo-Europeans, Chinese and Japanese. Finally, how could we manage out there without our mothers – where could we go, and who would be willing to hide us?

One day we were playing behind our house when we suddenly heard loud screaming. We immediately opened our spyhole, no longer caring that our secret would be revealed. An Indonesian man was tied to the large tree in the middle of the grass, and Japanese men were beating him. Just as we were about to shout through the hole for them to stop, some grown-ups, including our mother, ran up and pulled us away. They were completely confused, and all began talking at once. We were taken to the front of our house where we could no longer hear the sound. Someone said the white building was an opium factory that had been built by the Dutch; and someone else thought the Indonesian had stolen opium. What’s opium, we asked – why would anyone want to steal it? Because it makes you relaxed and happy, someone else replied, so you don’t feel your misery. Do you eat it? No, it’s a bit like smoking cigarettes.

Our mother tried to reassure us – the man must have done something really bad, and they must have stopped beating him by now. But then we were joined by other mothers who had seen what was happening, and they said the Indonesian had not only been beaten, but burned with lighted cigarettes. Everyone was shocked, but we weren’t allowed to return to our spyhole, and we tried to forget about it. I remember thinking ‘maybe the opium will help him feel it less’.

The next day we heard from our aunt that the Indonesian had been left tied to the tree all night, half-hanging from it, so in fact it was a gallows. She hadn’t been able to sleep for thinking about it. Eventually she couldn’t take it any more, found a ladder and quietly climbed over the fence to give him a cup of water. But when she reached him, he said quietly in Indonesian ‘No, madam, you mustn’t, it’s dangerous for you! You’ll get into trouble!’ But she gave him the water anyway, and he drank it.

Incredible that someone in such a terrible state felt he should warn someone who wanted to help him just how much of a risk she was taking. He knew what the Japanese were capable of, and took the risk that she would go back without giving him the water. I thought it was really brave of my aunt, and expected everyone else to agree. But in the days that followed I felt confused by what I heard people saying. Yes, she had been brave – but also reckless, just as everyone knew she was, always doing things differently from everyone else. She had put the whole camp in danger, for if anyone had done something they shouldn’t, we were all punished – forced to attend roll-call in the sun without water for hours on end, or not being fed for a whole day. I knew all this, but I thought it was so sweet of her to think of the man; no-one else had done it, and no-one else would have dared. Did the others perhaps feel they should have done it – were they in fact embarrassed by her courage?

But then, for the first time in my life, I heard something I could only give a name to much later: outright racism. I heard someone say you should never have done such a thing for an Indonesian – she used the contemptuous Dutch term inlander (‘native’) that was customary under the colonial regime. The only person to contradict her was my mother, who said it wasn’t fair. In pre-war colonial times the Dutch had been superior to the Indonesians, they had had the power and the important positions, and this had even been laid down by law. In retrospect, it seems so amazing to me that these women still had such ideas and feelings, now that they had been prisoners of the Japanese for so long and knew for themselves what it was like to be the target of racism.

Batavia, Weltevreden opium factory (1910)

We don’t know if there was any connection with this event, but soon afterwards the Japanese put an end to our secret glimpses of freedom. They built a second fence behind ours, all the way round the camp. But what about the white building we had seen in the distance? It was indeed an opium factory that the Dutch had built back in 1904, calling it the Weltevreden (‘content’, with overtones of ‘peaceful’) opium factory.

On a 1942 map of Batavia I have marked the site of the factory, a rectangular building with a central courtyard, in red. The other red line shows the camp fences round the streets that formed the Kramat-Zuid camp. The back gardens in our street, which was called Nieuwelaan, were right beside that line. Next to the fence is the open space where we saw the tree with the Indonesian tied to it. The open space, which in turn adjoined the factory site, was criss-crossed by a few streets. One of them was a cul-de-sac which the Indonesian population had nicknamed Gang Obat (‘Medicine Alley’) – ‘medicine’ sounded less dangerous than ‘opium’ (candu in Indonesian). A branch of one of the railway lines through Batavia ended in the middle of the factory site, so that the raw opium could be brought right up to the factory by goods train and taken away again after processing. The map also shows the Ciliwung river winding its way past the camp – depending on the weather, we could sometimes hear it flowing.

The 25 October 2017 edition of the Dutch news site De Correspondent (2 explains how the opium factory came to be built there in 1904. Ewald Vanvugt has devoted an in-depth study to the Dutch colonial regime’s centuries-long use of the opium trade to enrich itself at the expense of the Indonesian population’s health. This had begun back in the days of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), when ships’ captains en route to the East Indies purchased raw opium in Turkey, Persia and India, for trading purposes rather than their own consumption. Chinese traders were sold licences to process it and sell it in their opium dens.

The Dutch had imposed a monopoly on this opium trade, and used the vast profits to pay colonial officials and, above all, deploy soldiers to expand their colonial territory. New monopolies were imposed on the opium trade in the newly acquired territories, and this went on for two centuries, until the Dutch began to fear the Chinese traders’ increased wealth and power. They then got rid of the Chinese middlemen by taking over both the processing of the opium and the retail trade, and giving it a legal basis. Their intention was to make a product ‘to the taste of local users’, and this required a factory, which they called the Weltevreden opium factory. Permanently employed officials now sold this ‘legal opium’ to the by now numerous users.

The memories I have described here form the basis for the three stone sculptures I carved: the Belgian bluestone wall that represents the fence of the camp, my aunt’s ladder as a spiral staircase in Anröchte limestone, and the alabaster gallows tree to which the Indonesian was tied because he had stolen opium.

Map of Batavia 1942

1) Bep Rietveld’s paintings, and above all her wartime drawings, were exhibited at Museum Flehite in Amersfoort from 16 August 2020 to 24 January 2021: https://museumflehite.nl/tentoonstellingen/bep-rietveld/

2) https://decorrespondent.nl/7514/nederland-runde-eeuwenlang-een-drugskartel-en-betaalde-er-zijn-oorlogen-mee/2864549513826-9cf3bcd8 and Ewald Vanvugt, Wettig opium: 350 jaar Nederlandse opiumhandel in de Indische archipel, (‘Legal opium: 350 years of Dutch opium trading in the Indonesian archipelago’), Amsterdam, 1985, with an introduction by my father Wim F. Wertheim.